Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestionsObjectives

- How can I or my team work on multiple features in parallel?

- How to combine the changes of parallel tracks of work?

- How can I permanently reference a point in history, like a software version?

- Be able to create and merge branches.

- Know the difference between a branch and a tag.

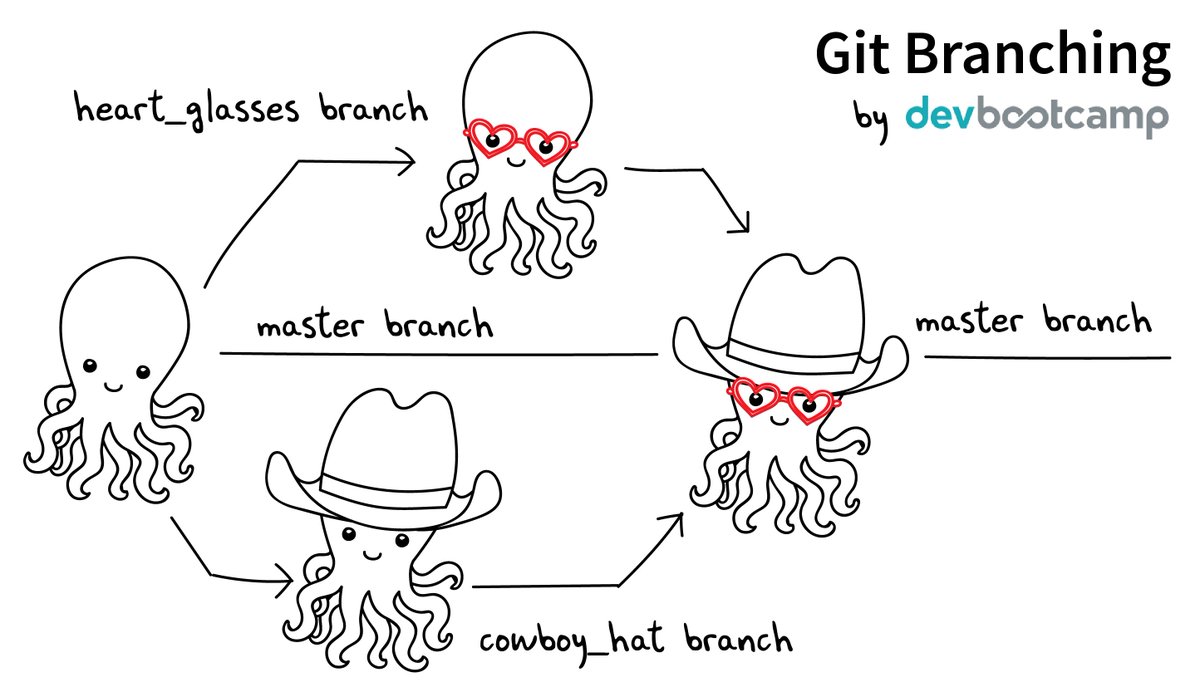

Motivation for branches

In the previous section we tracked a guacamole recipe with Git.

Up until now our repository had only one branch with one commit coming after the other:

- Commits are depicted here as little boxes with abbreviated hashes.

- Here the branch

masterpoints to a commit. - “HEAD” is the current position (remember the recording head of tape recorders?).

- When we talk about branches, we often mean all parent commits, not only the commit pointed to.

Now we want to do this:

Software development is often not linear:

- We typically need at least one version of the code to “work” (to compile, to give expected results, …).

- At the same time we work on new features, often several features concurrently. Often they are unfinished.

- We need to be able to separate different lines of work really well.

The strength of version control is that it permits the researcher to isolate different tracks of work, which can later be merged to create a composite version that contains all changes:

- We see branching points and merging points.

- Main line development is often called

master. - Other than this convention there is nothing special about

master, it is just a branch. - Commits form a directed acyclic graph (we have left out the arrows to avoid confusion about the time arrow).

A group of commits that create a single narrative are called a branch. There are different branching strategies, but it is useful to think that a branch tells the story of a feature, e.g. “fast sequence extraction” or “Python interface” or “fixing bug in matrix inversion algorithm”.

A useful alias

We will now define an alias in Git, to be able to nicely visualize branch structure in the terminal without having to remember a long Git command (more details about aliases are given in a later section):

$ git config --global alias.graph "log --all --graph --decorate --oneline"

Let us inspect the project history using the git graph alias:

$ git graph

* dd4472c (HEAD -> master) we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

- We have three commits (we use the first two characters of the commits) and only

one development line (branch) and this branch is called

master. - Commits are states characterized by a 40-character hash (checksum).

git graphprint abbreviations of these checksums.- Branches are pointers that point to a commit.

- Branch

masterpoints to commitdd4472c8093b7bbcdaa15e3066da6ca77fcabadd. HEADis another pointer, it points to where we are right now (currentlymaster)

On which branch are we?

To see where we are (where HEAD points to) use git branch:

$ git branch

* master

- This command shows where we are, it does not create a branch.

- There is only

masterand we are onmaster(star represents theHEAD).

In the following we will learn how to create branches, how to switch between them, how to merge branches, and how to remove them afterwards.

Creating and working with branches

Let’s create a branch called experiment where we add cilantro to ingredients.txt.

$ git branch experiment # create branch called "experiment" pointing to the present commit

$ git checkout experiment # switch to branch "experiment"

$ git branch # list all local branches and show on which branch we are

- Verify that you are on the

experimentbranch (note thatgit graphalso makes it clear what branch you are on:HEAD -> branchname):

$ git branch

* experiment

master

- Then add 2 tbsp cilantro on top of the

ingredients.txt:

* 2 tbsp cilantro

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 2 tsp salt

* 1/2 onion

- Stage this and commit it with the message “let us try with some cilantro”.

- Then reduce the amount of cilantro to 1 tbsp, stage and commit again with “maybe little bit less cilantro”.

We have created two new commits:

$ git graph

* 6feb49d (HEAD -> experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

* 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

* dd4472c (master) we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

- The branch

experimentis two commits ahead ofmaster. - We commit our changes to this branch.

Interlude: Different meanings of “checkout”

Depending on the context

git checkoutcan do very different actions:1) Switch to a branch:

$ git checkout <branchname>2) Bring the working tree to a specific state (commit):

$ git checkout <hash>3) Set a file/path to a specific state (throws away all unstaged/uncommitted changes):

$ git checkout <path/file>This is unfortunate from the user’s point of view but the way Git is implemented it makes sense. Picture

git checkoutas an operation that brings the working tree to a specific state. The state can be a commit or a branch (pointing to a commit).In latest Git this is much nicer:

$ git switch <branchname> # switch to a different branch $ git restore <path/file> # discard changes in working directory

Exercise: branches

- Change to the branch

master.- Create another branch called

less-saltwhere you reduce the amount of salt.- Commit your changes to the

less-saltbranch.Use the same commands as we used above.

We now have three branches (in this case

HEADpoints toexperiment):$ git branch * experiment less-salt master $ git graph * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt | * 6feb49d (HEAD -> experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro | * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro |/ * dd4472c (master) we should not forget to enjoy * 2bb9bb4 add half an onion * 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructionsHere is a graphical representation of what we have created:

- Now switch to

master.- Add and commit the following

README.mdtomaster:# Guacamole recipe Used in teaching Git.Now you should have this situation:

$ git graph * 40fbb90 (HEAD -> master) draft a readme | * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt |/ | * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro | * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro |/ * dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy * 2bb9bb4 add half an onion * 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

And for comparison this is how it looks on GitHub.

Merging branches

If you got stuck in the above exercises:

- Skip this unless you got stuck.

- Step out of the current directory:

$ cd .. $ git clone https://github.com/coderefinery/recipe.git recipe-branching$ cd recipe-branching$ git checkout experiment$ git checkout less-salt$ git checkout master$ git graph- Or call a helper to un-stuck it for you.

It turned out that our experiment with cilantro was a good idea.

Our goal now is to merge experiment into master.

First we make sure we are on the branch we wish to merge into:

$ git branch

experiment

less-salt

* master

Then we merge experiment into master:

$ git merge experiment

We can verify the result in the terminal:

$ git graph

* c43b24c (HEAD -> master) Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

| * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

What happens internally when you merge two branches is that Git creates a new commit, attempts to incorporate changes from both branches and records the state of all files in the new commit. While a regular commit has one parent, a merge commit has two (or more) parents.

To view the branches that are merged into the current branch we can use the command:

$ git branch --merged

experiment

* master

We are also happy with the work on the less-salt branch. Let us merge that

one, too, into master:

$ git branch # make sure you are on master

$ git merge less-salt

We can verify the result in the terminal:

$ git graph

* 4f00317 (HEAD -> master) Merge branch 'less-salt'

|\

| * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt

* | c43b24c Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| * | 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * | 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

| |/

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

Observe how Git nicely merged the changed amount of salt and the new ingredient in the same file without us merging it manually:

$ cat ingredients.txt

* 1 tbsp cilantro

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 1 tsp salt

* 1/2 onion

If the same file is changed in both branches, Git attempts to incorporate both changes into the merged file. If the changes overlap then the user has to manually settle merge conflicts (we will do that later).

Deleting branches safely

Both feature branches are merged:

$ git branch --merged

experiment

less-salt

* master

This means we can delete the branches:

$ git branch -d experiment less-salt

Deleted branch experiment (was 6feb49d).

Deleted branch less-salt (was bf59be6).

This is the result:

Compare in the terminal:

$ git graph

* 4f00317 (HEAD -> master) Merge branch 'less-salt'

|\

| * bf59be6 reduce amount of salt

* | c43b24c Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| * | 6feb49d maybe little bit less cilantro

| * | 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

| |/

* | 40fbb90 draft a readme

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

As you see only the pointers disappeared, not the commits.

Git will not let you delete a branch which has not been reintegrated unless you

insist using git branch -D. Even then your commits will not be lost but you

may have a hard time finding them as there is no branch pointing to them.

Exercise: encounter a fast-forward merge

- Create a new branch from

masterand switch to it.Create a couple of commits on the new branch (for instance edit

README.md):

- Now switch to

master.- Merge the new branch to

master.- Examine the result with

git graph.- Have you expected the result? Discuss what you see.

The following exercises are advanced, absolutely no problem to postpone them to a few months later. If you give them a go, keep in mind that you might run into conflicts, which we will learn to resolve in the next section.

(Optional) Exercise: Moving commits to another branch

Sometimes it happens that we commit to the wrong branch, e.g. to

masterinstead of a feature branch. This can easily be fixed by branching off, and then usinggit reset --hard:

- Make a couple of commits to

master, then realize these should have been on a new feature branch.- Create a new branch from

master, and rewindmasterback usinggit reset --hard <hash>.- Inspect the situation with

git graph. Problem solved!

(Optional) Exercise: Rebasing

As an alternative to merging branches, one can also rebase branches. Rebasing means that the new commits are replayed on top of another branch (instead of creating an explicit merge commit). Note that rebasing changes history and should not be done on public commits!

- Create a new branch, and make a couple of commits on it.

- Switch back to

master, and make a couple of commits on it.- Inspect the situation with

git graph.- Now rebase the new branch on top of

masterby first switching to the new branch, and thengit rebase master.- Inspect again the situation with

git graph. Notice that the commit hashes have changed - think about why!

(Optional) Exercise: Squashing commits

Sometimes you may want to squash incomplete commits, particularly before merging or rebasing with another branch (typically

master) to get a cleaner history. Note that squashing changes history and should not be done on public commits!

- Create two small but related commits on a new feature branch, and inspect with

git graph.- Do a soft reset with

git reset --soft HEAD~2. This rewinds the current branch by two commits, but keeps all changes and stages them.- Inspect the situation with

git graph,git statusandgit diff --staged.- Commit again with a commit message describing the changes.

- What do you think happens if you instead do

git reset --soft <hash>?

Summary

Let us pause for a moment and recapitulate what we have just learned:

$ git branch # see where we are

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git checkout <name> # switch to branch <name>

$ git merge <name> # merge branch <name> (to current branch)

$ git branch -d <name> # delete branch <name>

$ git branch -D <name> # delete unmerged branch

Since the following command combo is so frequent:

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git checkout <name> # switch to branch <name>

There is a shortcut for it:

$ git checkout -b <name> # create branch <name> and switch to it

Typical workflows

With this there are two typical workflows:

$ git checkout -b new-feature # create branch, switch to it

$ git commit # work, work, work, ...

# test

# feature is ready

$ git checkout master # switch to master

$ git merge new-feature # merge work to master

$ git branch -d new-feature # remove branch

Sometimes you have a wild idea which does not work. Or you want some throw-away branch for debugging:

$ git checkout -b wild-idea

# work, work, work, ...

# realize it was a bad idea

$ git checkout master

$ git branch -D wild-idea # it is gone, off to a new idea

# -D because we never merged back

No problem: we worked on a branch, branch is deleted, master is clean.

(Optional) Tags

- A tag is a pointer to a commit but in contrast to a branch it does not move.

- We use tags to record particular states or milestones of a project at a given point in time, like for instance versions (have a look at semantic versioning, v1.0.3 is easier to understand and remember than 64441c1934def7d91ff0b66af0795749d5f1954a).

- There are two basic types of tags: annotated and lightweight.

- Use annotated tags since they contain the author and can be cryptographically signed using GPG, timestamped, and a message attached.

Let’s add an annotated tag to our current state of the guacamole recipe:

$ git tag -a nobel-2017 -m "recipe I made for the 2017 Nobel banquet"As you may have found out already,

git showis a very versatile command. Try this:$ git show nobel-2017For more information about tags see for example the Pro Git book chapter on the subject.

Test your understanding

- Which of the following combos (one or more) creates a new branch and makes a commit to it? 1.

$ git branch new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit2.

$ git add file.txt $ git branch new-branch $ git checkout new-branch $ git commit3.

$ git checkout -b new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit4.

$ git checkout new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit- What is a detached

HEAD?- What are orphaned commits?

Solutions

- Both 2 and 3 would do the job. Note that in 2 we first stage the file, and then create the branch and commit to it. In 1 we create the branch but do not switch to it, while in 4 we don’t give the

-bflag togit checkoutto create the new branch.- When you check out a branch name, HEAD will point to the most recent commit of that branch. You can however check out a particular hash. This will bring your working directory back in time to that commit, and your HEAD will be pointing to that commit but it will not be attached to any branch. If you want to make commits in that state, you should instead create a new branch:

git checkout -b test-branch <hash>.- An orphaned commit is a commit that does not belong to any branch, and therefore doesn’t have any parent commits. This could happen if you make a commit in a detached HEAD state. Commits rarely vanish in Git, and you could still find the orphaned commit using

git reflog.

Key Points

A branch is a division unit of work, to be merged with other units of work.

A tag is a pointer to a moment in the history of a project.