List of exercises

Contents

List of exercises#

Summary#

Basics:

Branching and merging:

Conflict resolution:

Inspecting history:

Using the Git staging area:

Undoing and recovering:

Interrupted work:

Full list#

This is a list of all exercises and solutions in this lesson, mainly as a reference for helpers and instructors. This list is automatically generated from all of the other pages in the lesson. Any single teaching event will probably cover only a subset of these, depending on their interests.

Motivation#

Solution

Giving a version to a collaborator and merging changes later with own changes sounds like lots of work.

What if you discover a bug and want to know since when the bug existed?

Basics#

Basic-1: Record changes

Add 1/2 onion to ingredients.txt and also the instruction

to “enjoy!” to instructions.txt. Do not stage the changes yet.

When you are done editing the files, try git diff:

$ git diff

You will see (can you identify in there the two added lines?):

diff --git a/ingredients.txt b/ingredients.txt

index 2607525..ec0abc6 100644

--- a/ingredients.txt

+++ b/ingredients.txt

@@ -1,3 +1,4 @@

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 2 tsp salt

+* 1/2 onion

diff --git a/instructions.txt b/instructions.txt

index 6a8b2af..f7dd63a 100644

--- a/instructions.txt

+++ b/instructions.txt

@@ -3,3 +3,4 @@

* squeeze lime

* add salt

* and mix well

+* enjoy!

Now first stage and commit each change separately (what happens when we leave out the -m flag?):

$ git add ingredients.txt

$ git commit -m "add half an onion"

$ git add instructions.txt

$ git commit # <-- we have left out -m "..."

When you leave out the -m flag, Git should open an editor where you can edit

your commit message. This message will be associated and stored with the

changes you made. This message is your chance to explain what you’ve done and

convince others (and your future self) that the changes you made were

justified. Write a message and save and close the file.

When you are done committing the changes, experiment with these commands:

$ git log

$ git log --stat

$ git log --oneline

(optional) Basic-2: Comparing and showing commits

Inspect differences between commit hashes with

git diff <hash1> <hash2>.Have a look at specific commits with

git show <hash>.

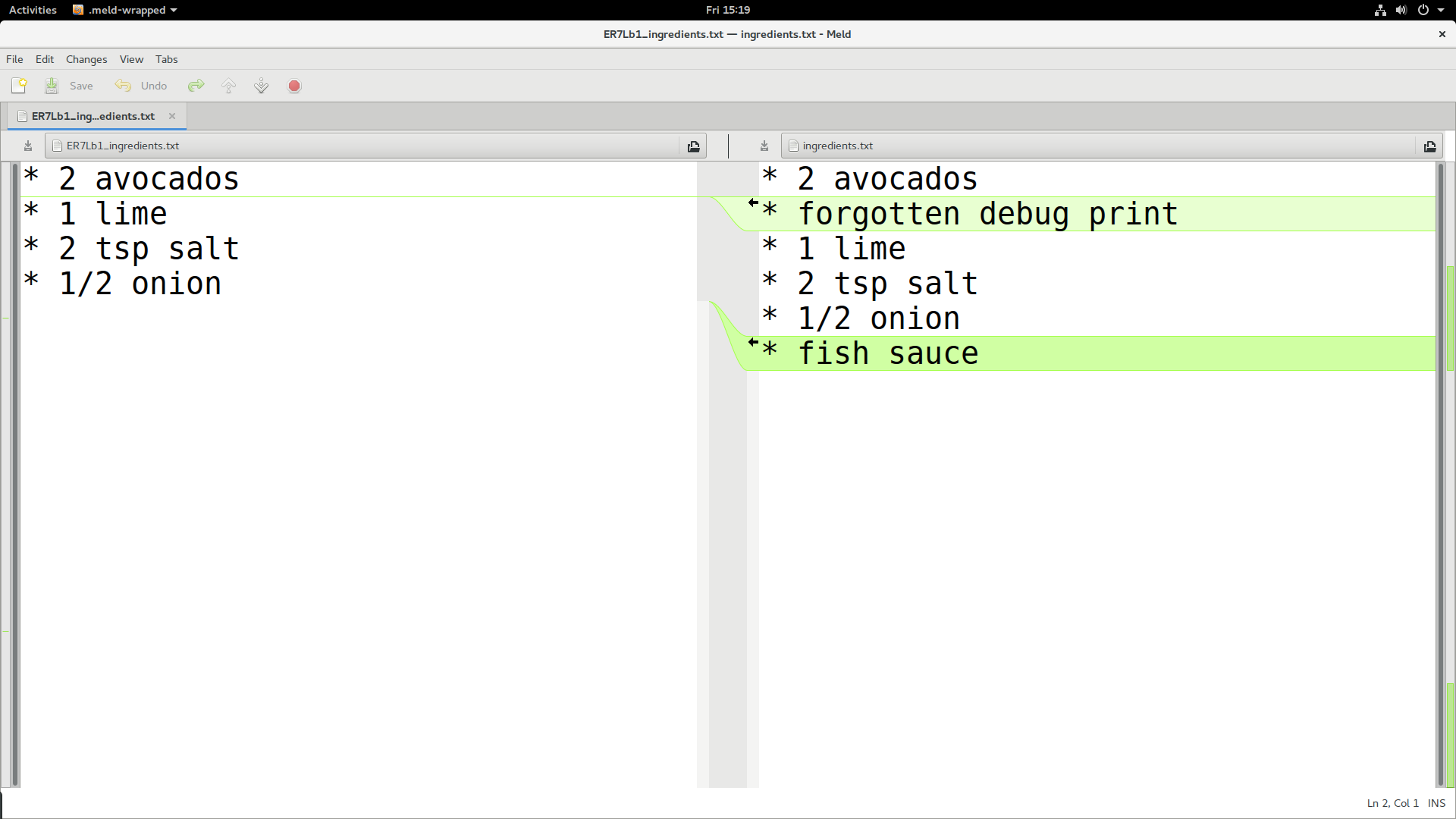

(optional) Basic-3: Visual diff tools

Make further modifications and experiment with

git difftool(requires installing one of the visual diff tools):

On Windows or Linux:

$ git difftool --tool=meld <hash>

On macOS:

$ git difftool --tool=opendiff <hash>

Git difftool using meld.#

You probably want to use the same visual diff tool every time and you can configure Git for that:

$ git config --global diff.tool meld

(optional) Basic-4: Renaming and removing files

Create a new file,

git addandgit committhe file.Rename the file with

git mv(you will need togit committhe rename).Use

git log --onelineandgit status.Remove the file with

git rm(again you need togit committhe change).Inspect the history with

git log --stat.

Basic-5: Test your understanding

Which command(s) below would save the changes of myfile.txt

to an existing local Git repository?

$ git commit -m "my recent changes"

$ git init myfile.txt $ git commit -m "my recent changes"

$ git add myfile.txt $ git commit -m "my recent changes"

$ git commit -m myfile.txt "my recent changes"

Solution

Would only create a commit if files have already been staged.

Would try to create a new repository in a folder “myfile.txt”.

Is correct: first add the file to the staging area, then commit.

Would try to commit a file “my recent changes” with the message myfile.txt.

Branching and merging#

Branch-1: Create and commit to branches

In this exercise, you will create another new branch and few more commits. We will use this in the next section, to practice merging.

Change to the branch

master.Create another branch called

less-saltNote! makes sure you are on master branch when you create the less-salt branch

A safer way would be to explicitly mention to create from the master branch as shown below

$ git branch less-salt master

Where you reduce the amount of salt.

Commit your changes to the

less-saltbranch.

Use the same commands as we used above.

We now have three branches (in this case HEAD points to less-salt):

$ git branch

experiment

* less-salt

master

$ git graph

* bf59be6 (HEAD -> less-salt) reduce amount of salt

| * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

|/

* dd4472c (master) we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

Here is a graphical representation of what we have created:

Now switch to

master.Add and commit the following

README.mdtomaster:

# Guacamole recipe

Used in teaching Git.

Now you should have this situation:

$ git graph

* 40fbb90 (HEAD -> master) draft a readme

| * bf59be6 (less-salt) reduce amount of salt

|/

| * 6feb49d (experiment) maybe little bit less cilantro

| * 7cf6d8c let us try with some cilantro

|/

* dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

* 2bb9bb4 add half an onion

* 2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

And for comparison this is how it looks on GitHub.

(optional) Branch-2: Perform a fast-forward merge

Create a new branch from

masterand switch to it.Create a couple of commits on the new branch (for instance edit

README.md):Now switch to

master.Merge the new branch to

master.Examine the result with

git graph.Have you expected the result? Discuss what you see.

Solution

You will see that in this case no merge commit was created and Git merged the two branches by moving (fast-forwarding) the “master” branch (label) three commits forward.

This was possible since one branch is the ancestor of the other and their developments did not diverge.

A merge that does not require any merge commit is a fast-forward merge.

(optional) Branch-3: Rebase a branch (instead of merge)

As an alternative to merging branches, one can also rebase branches. Rebasing means that the new commits are replayed on top of another branch (instead of creating an explicit merge commit). Note that rebasing changes history and should not be done on public commits!

Create a new branch, and make a couple of commits on it.

Switch back to

master, and make a couple of commits on it.Inspect the situation with

git graph.Now rebase the new branch on top of

masterby first switching to the new branch, and thengit rebase master.Inspect again the situation with

git graph. Notice that the commit hashes have changed - think about why!

Solution

You will notice two things:

History is now linear and does not contain merge commits.

All the commit hashes that were on the branch that got rebased, have changed. This also demonstrates that

git rebaseis a command that alters history. The commit history looks as if the rebased commits were all done after themastercommits.

Branch-4: Test your understanding

Which of the following combos (one or more) creates a new branch and makes a commit to it?

$ git branch new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit

$ git add file.txt $ git branch new-branch $ git checkout new-branch $ git commit

$ git checkout -b new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit

$ git checkout new-branch $ git add file.txt $ git commit

Solution

Both 2 and 3 would do the job. Note that in 2 we first stage the file, and then create the

branch and commit to it. In 1 we create the branch but do not switch to it, while in 4 we

don’t give the -b flag to git checkout to create the new branch.

Conflict resolution#

Conflict-1: Create another conflict and resolve

In this exercise, we repeat almost exactly what we did above with a different ingredient.

Create two branches before making any modifications.

Again modify some ingredient on both branches.

Merge one, merge the other and observe a conflict, resolve the conflict and commit the merge.

What happens if you apply the same modification on both branches?

If you create a branch

like-avocados, commit a change, then from this branch create another banchdislike-avocados, commit again, and try to merge both branches intomasteryou will not see a conflict. Can you explain, why it is different this time?

Solution

4: No conflict in this case if the change is the same.

5: No conflict in this case since in Git history one change happened after the other. The two changes are related and linked by Git history and one is a Git ancestor of the other. Git will assume that since we applied one change after the other, we meant this. There is nothing to resolve.

(optional) Conflict-2: Resolve a conflict when rebasing a branch

Create two branches where you anticipate a conflict.

Try to merge them and observe that indeed they conflict.

Abort the merge with

git merge --abort.What do you expect will happen if you rebase one branch on top of the other? Do you anticipate a conflict? Try it out.

Solution

Yes, this will conflict. If it conflicts during a merge, it will also conflict

during rebase but the conflict resolution looks slightly different:

You still need to look for conflict markers but you tell Git that you resolved

a conflict with git add and then you continue with git rebase --continue.

Follow instructions that you get from the Git command line.

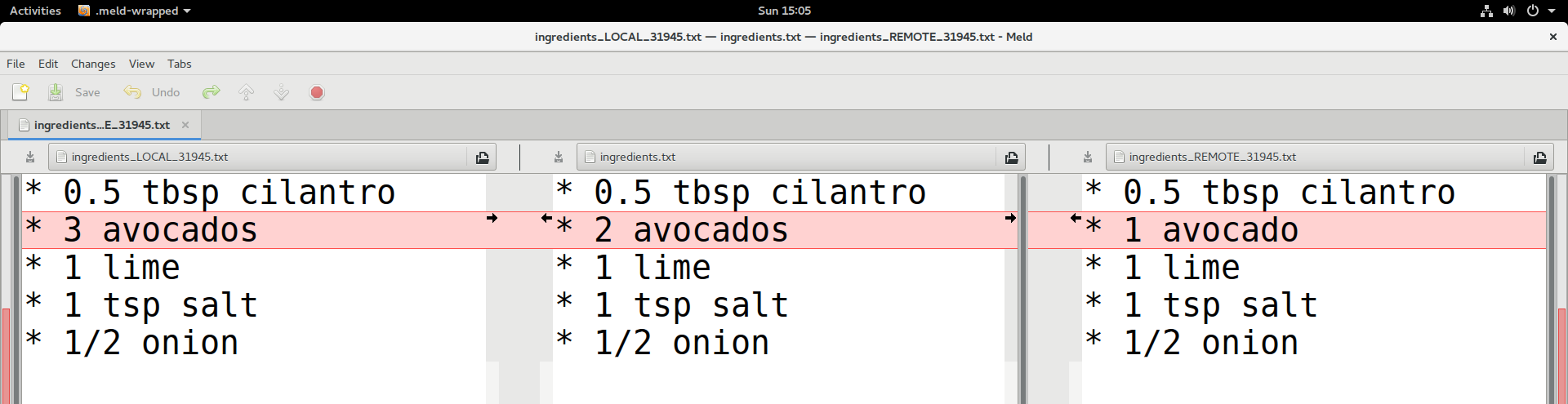

(optional) Conflict-3: Resolve a conflict using mergetool

Again create a conflict (for instance disagree on the number of avocados).

Stop at this stage:

Auto-merging ingredients.txt CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in ingredients.txt Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Instead of resolving the conflict manually, use a visual tool (requires installing one of the visual diff tools):

$ git mergetool

Your current branch is left, the branch you merge is right, result is in the middle.

After you are done, close and commit,

git addis not needed when usinggit mergetool.

If you have not instructed Git to avoid creating backups when using mergetool, then to be on the safe side there will be additional temporary files created. To remove those you can do a git clean after the merging.

To view what will be removed:

$ git clean -n

To remove:

$ git clean -f

To configure Git to avoid creating backups at all:

$ git config --global mergetool.keepBackup false

Inspecting history#

History-1: Explore basic archaeology commands

Let us explore the value of these commands in an exercise. Future exercises do not depend on this, so it is OK if you do not complete it fully.

In-person workshops: We recommend that you do this exercise in groups of two and discuss with your neighbors.

Video workshops: We will group you in breakout rooms of ~4 persons where you can work and discuss together. A helper or instructor will pop in to help out. In the group one participant can share their screen and others in the group help out, discuss, and try to follow along. Please write down questions in the collaborative notes. After 15-20 minutes we will bring you back into the main room and discuss.

Exercise steps:

Clone this repository: https://github.com/networkx/networkx.git. Then step into the new directory and create an exercise branch from the networkx-2.6.3 tag/release:

$ git clone https://github.com/networkx/networkx.git $ cd networkx $ git checkout -b exercise networkx-2.6.3

Then using the above toolbox try to:

Find the code line which contains

"Logic error in degree_correlation".Find out when this line was last modified or added. Find the actual commit which modified that line.

Inspect that commit with

git show.Create a branch pointing to the past when that commit was created to be able to browse and use the code as it was back then.

How would can you bring the code to the commit precisely before that line was last modified?

Solution

We use

git grep:$ git grep "Logic error in degree_correlation"

This gives the output:

networkx/algorithms/threshold.py: print("Logic error in degree_correlation", i, rdi)

Maybe you also want to know the line number:

$ git grep -n "Logic error in degree_correlation"

We use

git annotate:$ git annotate networkx/algorithms/threshold.pyThen search for “Logic error” by typing “/Logic error” followed by Enter. The last commit that modified it was

90544b4fa(unless that line changed since).We use

git show:$ git show 90544b4faCreate a branch pointing to that commit (here we called the branch “past-code”):

$ git branch past-code 90544b4faThis is a compact way to access the first parent of

90544b4fa(here we called the branch “just-before”):$ git checkout -b just-before 90544b4fa~1

(optional) History-2: Use git bisect to find the bad commit

In this exercise, we use git bisect on an example repository. It

is OK if you do not complete this exercise fully.

Begin by cloning https://github.com/coderefinery/git-bisect-exercise.

Motivation

The motivation for this exercise is to be able to do archaeology with Git on a source code where the bug is difficult to see visually. Finding the offending commit is often more than half the debugging.

Background

The script get_pi.py approximates pi using terms of the Nilakantha series. It

should produce 3.14 but it does not. The script broke at some point and

produces 3.57 using the last commit:

$ python get_pi.py

3.57

At some point within the 500 first commits, an error was introduced. The only thing we know is that the first commit worked correctly.

Your task

Clone this repository and use

git bisectto find the commit which broke the computation (solution - spoiler alert!).Once you have found the offending commit, also practice navigating to the last good commit.

Bonus exercise: Write a script that checks for a correct result and use

git bisect runto find the offending commit automatically (solution - spoiler alert!).

Video workshops: We will group you in breakout rooms of ~4 persons where you can work and discuss together. A helper or instructor will pop in to help out. Please write down questions in the collaborative notes. After 15-20 minutes we will bring you back into the main room and discuss.

Hints

Finding the first commit:

$ git log --oneline | tail -n 1

How to navigate to the parent of a commit with hash somehash:

$ # create branch pointing to the parent of somehash

$ git checkout -b branchname somehash~1

$ # instead of a tilde you can also use this

$ git checkout -b branchname somehash^

Using the Git staging area#

Staging-1: Perform an interactive commit

One option to help us create nice logical commits is to stage interactively

with git commit --patch:

Make two changes in

instructions.txt, at the top and bottom of the file. Make sure that they are separated by at least several unmodified lines.Run

git commit --patch. Using the keystrokes above, commit one of the changes.Do it again for the other change.

When you’re done, inspect the situation with

git log,git status,git diffandgit diff --staged.When would this be useful?

Solution

This can be useful if you have several modification in a file (or several files) but you decide that it would be beneficial to save them as two (or more) separate commits.

Staging-2: Use the staging area to make a commit in two steps

In your recipe example, make two different changes to

ingredients.txtandinstructions.txtwhich do not go together.Use

git addto stage one of the changes.Use

git statusto see what’s going on, and usegit diffandgit diff --stagedto see the changes.Feel some regret and unstage the staged change.

Undoing and recovering#

Undoing-1: Revert a commit

Create a commit (commit A).

Revert the commit with

git revert(commit B).Inspect the history with

git log --oneline.Now try

git showon both the reverted (commit A) and the newly created commit (commit B).

Undoing-2: Modify a previous commit

Make an incomplete change to the recipe or a typo in your change,

git addandgit committhe incomplete/unsatisfactory change.Inspect the unsatisfactory but committed change with

git show. Remember or write down the commit hash.Now complete/fix the change but instead of creating a new commit, add the correction to the previous commit with

git add, followed bygit commit --amend. What changed?

Solution

One thing that has changed now is the commit hash. Modifying the previous commit has changed the history. This is OK to do on commits that other people don’t depend on yet.

Undoing-3: Destroy our experimentation in this episode

After we have experimented with reverts and amending, let us destroy all of that and get our repositories to a similar state.

First, we will look at our history (

git log/git graph) and find the last commit<hash>before our tests.Then, we will

git reset --hard <hash>to that.Then,

git graphagain to see what happened.

$ git log --oneline

d62ad3e (HEAD -> master) Revert "not sure this is a good idea"

f960dd3 not sure this is a good idea

dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

2bb9bb4 add half an onion

2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

$ git reset --hard dd4472c

HEAD is now at dd4472c we should not forget to enjoy

$ git log --oneline

dd4472c (HEAD -> master) we should not forget to enjoy

2bb9bb4 add half an onion

2d79e7e adding ingredients and instructions

Undoing-4: Test your understanding

What happens if you accidentally remove a tracked file with

git rm, is it gone forever?Is it OK to modify commits that nobody has seen yet?

What situations would justify to modify the Git history and possibly remove commits?

Solution

It is not gone forever since

git rmcreates a new commit. You can simply revert it!If you haven’t shared your commits with anyone it can be alright to modify them.

If you have shared your commits with others (e.g. pushed them to GitHub), only extraordinary conditions would justify modifying history. For example to remove sensitive or secret information.

Interrupted work#

Interrupted-1: Stash some uncommitted work

Make a change.

Check status/diff, stash the change, check status/diff again.

Make a separate, unrelated change which doesn’t touch the same lines. Commit this change.

Pop off the stash you saved, check status/diff.

Optional: Do the same but stash twice. Also check

git stash list. Can you pop the stashes in the opposite order?Advanced: What happens if stashes conflict with other changes? Make a change and stash it. Modify the same line or one right above or below. Pop the stash back. Resolve the conflict. Note there is no extra commit.

Advanced: what does

git graphshow when you have something stashed?

Solution

5: Yes you can. With git stash pop <index> you can decie which stash

index to pop.

6: In this case Git will ask us to resolve the conflict the same way when resolving conflicts between two branches.

7: It shows an additional commit hash with refs/stash.