Interactive teaching style

What are the top issues new instructors face?

Solution

Breaks are not negotiable, minimum 10 minutes.

Breakout sessions too short. Make them as long as possible, don’t expect to come back for new intro, then go back.

Get the speed correct. Not too fast and not too slow.

People will accomplish less than you expect. Expect learners to be 5 times slower than you, at best!

All the other tools and stuff will go wrong. Try to not bring in a dependency when you don’t need it.

Trying to accomplish too much: it’s OK to cut out and adapt to the audience. Have a reserve session at the end you prepare, but are ready to skip.

Explaining how, but not why.

Running out of time to making your environment match the learner’s.

Running out of time to set up good screen sharing practices

(terminal history, portion of screen, remote history) in advance.

Assuming learners remember what they have already learned, or know the prerequisites. Or have stuff installed and configured.

Not managing expectations: learners think that you will accomplish everything, and feel sad when you don’t.

Special issues when lessons delivered online (discussed during Workshop preparation and organization)

The Carpentries and CodeRefinery approaches to teaching

Here we will give you a very short overview of the Carpentries approach to teaching and highlight parts that are most important for teaching CodeRefinery style lessons.

Most CodeRefinery instructors have completed the Carpentry instructor training workshop, which anyone can apply for

This material

This section is derived from the Carpentries instructor training material. We encourage you to further study this material later, and to sign up for a 2-day Carpentry intructor training workshop.

Key principles

The “Carpentries” approach to teaching is based on:

Applying research-based teaching principles, especially as they apply to the Carpentries audience.

Understanding the importance of a respectful and inclusive classroom environment.

Carpentries teaching principles

Learners need to practice what they are learning in real time and get feedback on what they are doing. That is why the teaching approach relies on live coding.

Learners best learn in a respectful classroom environment, so the Carpentries use a Code of Conduct.

Learners are encouraged to help each other during workshops as this improves their confidence and reinforces concepts taught.

Carpentry instructors try to have learners do something that they think is useful in their daily work within 15 minutes of starting each lesson.

In CodeRefinery, we follow The Carpentries teaching principles but in addition to live coding we often use group discussions to put in context the concepts we are teaching.

Applying these teaching principles are not sufficient and in addition we need to be able to check the effectiveness of our methods.

On the importance of feedback

Feedback is an essential part of effective learning. Feedback is bi-directional:

To be effective, instructors need feedback on their learners’ progress. Learners can also check their progress and ask relevant questions to get clarification.

Instructors also need feedback on their teaching. For instance, this can help them to adapt the pace, add/skip optional exercises and improve their teaching.

Getting/giving feedback on learners’ progress

This feedback comes through what is called formative assessments (in contrast to summative assessment).

Summative Assessment

Summative assessment is used to judge whether a learner has reached an acceptable level of competence. Usually at the end of a course Learners either “pass” or “fail” a summative assessment. One example is a driving exam, which tells the rest of society whether someone can safely be allowed on the road. Most assessment done in university courses is summative, and is used to assign course grades.

Formative assessment

Formative assessment takes place during teaching and learning. It sounds like a fancy term, but it can be used to describe any interaction or activity that provides feedback to both instructors and learners about learners’ level of understanding of the material. For learners, this feedback can help focus their study efforts. For instructors, it allows them to refocus their instruction to respond to challenges that learners are facing. Used continuously

Learners don’t “pass” or “fail” formative assessments; they are simply a feedback mechanism. For example, a music teacher might ask a learner to play a scale very slowly in order to see whether they are breathing correctly, and if not, what they should change.

Formative assessment is most useful when it happens frequently (we’ll talk about how frequently later) and when the results are easily interpretable by the learner and instructor.

CodeRefinery uses different instruments to get feedback from learners:

Surveys: we will discuss about CodeRefinery pre/post-surveys in the episode Running a workshop: online.

Exercises: we have many exercises during CodeRefinery workshops and use polls too but not necessarily many multiple-choice questions. This is something that we may change in the future but the initial reason was that we build on existing knowledge (see below section on our target audience) and give recommendations for best software practices: there is no unique solution and you would like our learners to choose the approach that is most suitable for them. For the same reasons, we have many optional exercises to accommodate the different levels. We would like everyone to get something useful out of the CodeRefinery workshops.

Getting/giving feedback on teaching

Teaching is a skill. One of the objective of the CodeRefinery Instructor training is to give you the confidence in teaching CodeRefinery lessons. Later we will have group work where we will practice teaching some lessons.

Before doing so, we will learn here to give feedback on teaching using the same positive-vs-negative and content-vs-presentation rubric.

Give feedback on teaching (optional, 10 mn)

This exercise aims at learning to give feedback. It is optional as we have similar exercises when practising teaching). As a group, we will watch this video of teaching and give feedback on two axes: positive vs. negative and content vs. presentation. Have each person in the class add one point to a 2x2 grid on a whiteboard or in the shared notes (hackMD, etherpad, google doc) without duplicating any points. For online instructor training event, use breakout room (4-5 persons per group) to facilitate discussion. Then each group reports to the shared notes. You can use a rubric (used during The Carpentries teaching demos) to help you take notes. What did other people see that you missed? What did they think that you strongly agree or disagree with?

Who are the learners

The first task in teaching is to figure out who your learners are. The Carpentries approach is based on the work of researchers like Patricia Benner, who applied the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition in her studies of how nurses progress from novice to expert (see also books by Benner). This work indicates that through practice and formal instruction, learners acquire skills and advance through distinct stages. In simplified form, the three stages of this model are:

Novices, competent practitioners and experts

Novice: someone who doesn’t know what they don’t know, i.e., they don’t yet know what the key ideas in the domain are or how they relate. One sign that someone is a novice is that their questions “aren’t even wrong”.

Example: A novice learner in a Carpentries workshop might never have heard of the bash shell, and therefore may have no understanding of how it relates to their file system or other programs on their computer.

Example HPC: A learner who has never executed a program on remote computer in headless mode

Example HPC: A learner who has no understanding about using a queue system and having a hard time why a program can not be run directly after login in.

Competent practitioner: someone who has enough understanding for everyday purposes. They won’t know all the details of how something works and their understanding may not be entirely accurate, but it is sufficient for completing normal tasks with normal effort under normal circumstances.

Example: A competent practitioner in a Carpentries workshop might have used the shell before and understand how to move around directories and use individual programs, but they might not understand how they can fit these programs together to build scripts and automate large tasks.

Example: A competent practitioner in a CodeRefinery workshop is someone that understands the concepts of best software practices and its importance. He/she clearly sees the benefits of applying best software practices but he/she does not fully know yet how and what to use for their own projects.

Example HPC: Knows how to establish a connection to a cluster and have submitted jobs. But may not know how to request optimal amount of resources in a job and how to setup parallel jobs

Expert: someone who can easily handle situations that are out of the ordinary.

Example: An expert in a Carpentries workshop may have experience writing and running shell scripts and, when presented with a problem, immediately sees how these skills can be used to solve the problem.

Example HPC: A learner who has a good understanding of the queue system, parallel processing and understand how to interpret error reports when something goes wrong and knows how to get help.

Cognitive Development and Mental Models

Effective learning is facilitated by the creation of a well-founded mental model. A mental model is a collection of concepts and facts, along with the relationships between those concepts, which a person has about a topic. For example, a long-time resident of the United States may have an advanced understanding of the location of US states, major cities and landmarks, weather patterns, regional economies and demographic patterns, as well as the relationships among these, compared with their understanding of these relationships for other countries. In other words, their mental model of the United States is more complex compared with their mental model of other countries.

We can distinguish between a novice and a competent practitioner for a given domain based on the complexity of their mental models.

A novice is someone who has not yet built a mental model of the domain. They therefore reason by analogy and guesswork, borrowing bits and pieces of their mental models of other domains which seem superficially similar.

A competent practitioner is someone who has a mental model that’s good enough for everyday purposes. This model does not have to be completely accurate in order to be useful: for example, the average driver’s mental model of how a car works probably doesn’t include most of the complexities that a mechanical engineer would be concerned with.

We could expect a mixture of learners from novice and competent practitioner groups in HPC training events.

How “knowledge” gets in the way

Mental models are hardly ever built from scratch. Every learner comes to a topic with some amount of information, ideas and opinions about the topic. This is true even in the case where a learner can’t articulate their prior knowledge and beliefs.

In many cases, this prior knowledge is incomplete or inaccurate. Inaccurate beliefs can be termed “misconceptions” and can impede learning by making it more difficult for learners to incorporate new, correct information into their mental models. Correcting learners’ misconceptions is at least as important as presenting them with correct information. Broadly speaking, misconceptions fall into three categories:

Simple factual errors, such as believing that Vancouver is the capital of British Columbia. These are the easiest to correct.

Broken models, such as believing that motion and acceleration must be in the same direction. We can address these by having learners reason through examples to see contradictions.

Fundamental beliefs, such as “the world is only a few thousand years old” or “human beings cannot affect the planet’s climate”. These beliefs are deeply connected to the learner’s social identity and are the hardest to change.

The current HPC carpentry workshop material are aimed at Novice of HPC

Among Novice learners there might be learners who are experts in their domain and very competent in the program they are executing, but may not have used a HPC system before. Then among the competent practitioners There might be learners who repeat some procedures they have inherited but lack a in-depth understanding of what’s going on. That is why it is important to get accurate feedback, before and during the workshops to understand the learner profiles.

Exercise: How to identify learner profiles?

How to identify leaner profiles from surveys and during the class

Which types of learners should the leassons focus on

CodeRefinery Curriculum and Reverse Instructional Design (with recommendations for HPC carpentries)

When writing a CodeRefinery lesson, we take a “reverse” approach to instruction, as described in Wiggins and McTighe’s Understanding by Design, that keeps the focus firmly on learning outcomes. The order of preparation in this case becomes

Determine your learning objectives

Decide what constitutes evidence that objectives have been met, and design assessments to target that evidence

Design instruction: Sort assessments in order of increasing complexity, and write content that connects everything together

Working with learning objectives

Each CodeRefinery lesson (also the HPC capentries lessons) usually has a learning objectives section. Good learning objectives are quite specific about the intended effect of a lesson on its learners. We aim to create learning objectives that are specific, accurate, and informative for both learners and instructors.

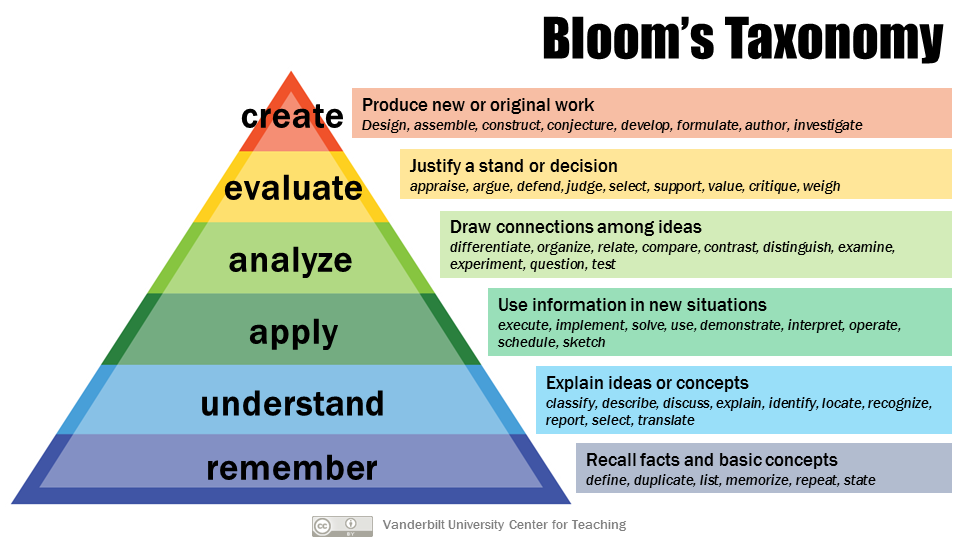

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to write effective learning objectives

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework for thinking about learning that breaks progress down into discrete, hierarchical steps. While many ideas have come and gone in education, Bloom’s has remained a useful tool for educators, in particular because the hierarchy seems to be reasonably valid: outcomes at the top of the hierarchy cannot be achieved without mastery of outcomes at the bottom. In the long term, everybody wants to be at the top. However, in aiming to meet learners where they are, we also need to be mindful about helping them to “grow a level,” helping them to recognize when they have achieved that growth, and guiding them to look ahead to where we might not be able to take them.

Image credit: Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching

Revisiting Learning objectives

When using existing teaching material, reverse instructional design principles might be applied as follows:

Review the lesson’s learning objectives carefully, thinking about how they will work for your audience

Scan the lesson to identify promising points to check in with your learners, using formative assessment to verify that objectives have been met

Review the connecting content in detail to be sure everything works and you have anticipated likely problems and questions.

We strongly encourage you to read them before teaching a lesson and to review whether they still match the content of the lesson: