Jupyter Notebooks

Objectives

Know what it is

Create a new notebook and save it

Open existing notebooks from the web

Be able to create text/markdown cells, code cells, images, and equations

Know when to use a Jupyter Notebook for a Python project and when perhaps not to

We will build up this notebook (spoiler alert!)

[this lesson is adapted from https://coderefinery.github.io/jupyter/motivation/]

Motivation for Jupyter Notebooks

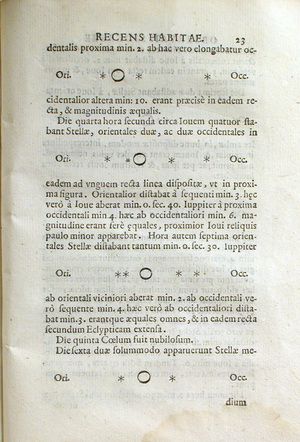

One of the first notebooks: Galileo’s drawings of Jupiter and its Medicean Stars from Sidereus Nuncius. Image courtesy of the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries (CC-BY).

Code, text, equations, figures, plots, etc. are interleaved, creating a computational narrative.

The name “Jupyter” derives from Julia+Python+R, but today Jupyter kernels exist for dozens of programming languages.

Our first notebook

Exercise Jupyter-1: Create a notebook (15 min)

Open a new notebook (on Windows: open Anaconda Navigator, then launch JupyterLab; on macOS/Linux: you can open JupyterLab from the terminal by typing

jupyter-lab)Rename the notebook

Create a markdown cell with a section title, a short text, an image, and an equation

# Title of my notebook Some text.  $E = mc^2$

Most important shortcut: Shift + Enter, to run current cell and create a new one below.

Create a code cell where you define the

arithmetic_meanfunction:def arithmetic_mean(sequence): s = 0.0 for element in sequence: s += element n = len(sequence) return s / n

In a different cell, call the function:

arithmetic_mean([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

In a new cell, let us try to plot a layered histogram:

# this example is from https://altair-viz.github.io/gallery/layered_histogram.html import pandas as pd import altair as alt import numpy as np np.random.seed(42) # Generating Data source = pd.DataFrame({ 'Trial A': np.random.normal(0, 0.8, 1000), 'Trial B': np.random.normal(-2, 1, 1000), 'Trial C': np.random.normal(3, 2, 1000) }) alt.Chart(source).transform_fold( ['Trial A', 'Trial B', 'Trial C'], as_=['Experiment', 'Measurement'] ).mark_bar( opacity=0.3, binSpacing=0 ).encode( alt.X('Measurement:Q').bin(maxbins=100), alt.Y('count()').stack(None), alt.Color('Experiment:N') )

Run all cells.

Save the notebook.

Observe that a “#” character has a different meaning in a code cell (code comment) than in a markdown cell (heading).

Your notebook should look like this one.

Use cases for notebooks

Really good for step-by-step recipes (e.g. read data, filter data, do some statistics, plot the results)

Experimenting with new ideas, testing new libraries/databases

As an interactive development environment for code, data analysis, and visualization

Keeping track of interactive sessions, like a digital lab notebook

Supplementary information with published articles

Good practices

Run all cells or even Restart Kernel and Run All Cells before sharing/saving to verify that the results you see on your computer were not due to cells being run out of order.

This can be demonstrated with the following example:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

arithmetic_mean(numbers)

We can first split this code into two cells and then re-define numbers

further down in the notebook. If we run the cells out of order, the result will

be different.